In the Ryukyu Islands, tin has long been used for ritual utensils and drinking containers. The highest level drinking containers, dedicated to the gods were also made of tin, such as uta-masuki, a sake bottle beaded with glass beads, and jihai, a sake cup decorated with ear-like ornaments.

A document from the mid-1400s records that tin was also used for the roof of Shuri Castle, and was essential for the distillation of awamori.

Toshinobu Uehara, a goldsmith, says, “Tin is easy to process and was probably suitable for the architecture of Ryukyu, which has been frequently hit by typhoons”.

Toshinobu Uehara, a goldsmith, says, “Tin is easy to process and was probably suitable for the architecture of Ryukyu, which has been frequently hit by typhoons”.

He actually showed us and how it was thinly stretched tin which was wrapped around a roof tile. It is highly corrosion resistant and does not rust even when exposed to sea breezes.

However, about 100 years ago, the tin culture of Ryukyu disappeared from history.

There is a craftsman who is currently trying to revive the Ryukyuan tin culture in the modern age. He is Mr. Toshinobu Uehara of “Kanzeku Matsu. Kanzeku means “goldsmith” in Ryukyuan language.

“My grandparents and father are from Okinawa, and I named my studio after my grandfather, who always wanted to return to his hometown. I started the workshop because I wanted to pass on to future generations the Okinawan tin culture, which is my roots, as something that has certainly existed there for a long time,” says Mr. Uehara.

An encounter with his roots in Okinawan tinware, his roots, changed his life.

Toshinobu Uehara, a goldsmith. At his workshop in Ginowan City.

Toshinobu Uehara, a goldsmith. At his workshop in Ginowan City.

Mr. Uehara studied metal crafts and design at a university and other institutions, and then studied as a craftsman of Takaoka copperware, a traditional craft in Toyama Prefecture. Takaoka produces copper wares such as Buddhist altar wares, tea ceremony utensils, flower vases, and even huge Buddhist bells and bronze statues. Mr. Uehara first encountered Okinawan tin culture in his sixth year of employment, when he was beginning to consider whether he should be as a craftsman in the future.

“I became a working adult and had saved up some money, so I decided to take my parents on a trip. The destination was Okinawa, my father’s birth place. Though It was a sightseeing trip, but as a craftsman, I was curious about the local metal crafts. Before the trip, I researched a lot of literature on metal work. That is when I first learned that there was a tin culture in Okinawa”.

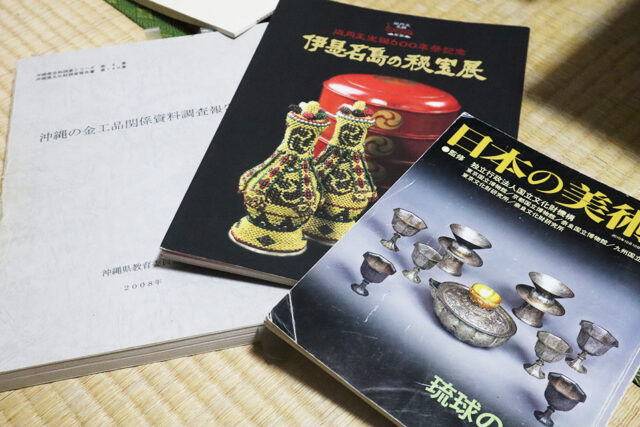

Then, Mr. Uehara collected some of the materials.

Then, Mr. Uehara collected some of the materials.

For research purposes, he has collected many materials and artifacts related to Ryukyuan crafts.

In between trips with his parents, Mr. Uehara asked curators about information he could not find on the Internet, and he brought back that information from the library after he researched documents there.

The following year, he visited Kyoko Awakuni, a researcher of Okinawan culture and crafts. This interaction with her led him becoming more and more fascinated with Ryukyuan tin culture, and he decided to begin his own fieldwork. While he continued his work in Takaoka, he found time to often visit Okinawa.

“The more I researched Ryukyuan tin culture, the more I found out that they have very high processing techniques and treat tin with great care. At the same time, I felt frustrated that they were not being properly appreciated, and I felt a strong desire to make it my life’s work to pass tin culture onto people.”

Moving to Okinawa and starting a workshop

Chinanago (garden eel)a pen stand made by Mr. Uehara.

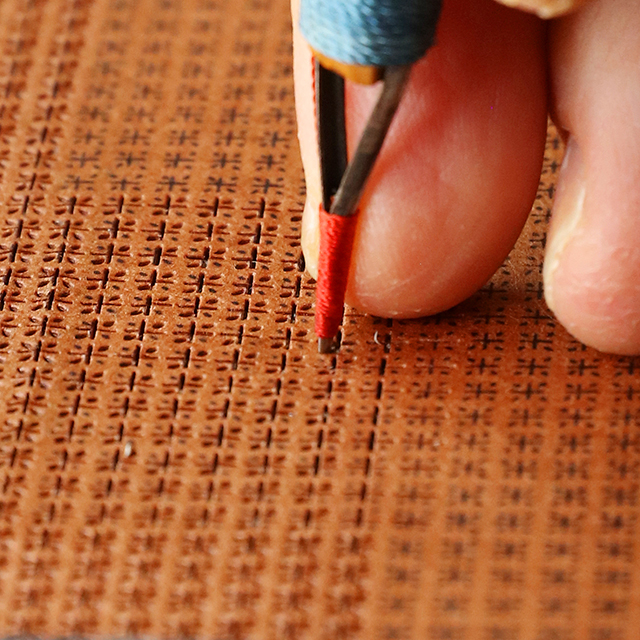

Because tin is soft, it can be bent by hand to change its structure.

In 2015, Mr. Uehara moved to Okinawa and started his workshop with no experience, no contacts, and no standing. First, he applied for the industry, and received support from various experts and learned in detail rudimentary knowledge such as management, cost accounting, and sales channel development.

I really wanted to reproduce and offer traditional Ryukyuan tinware, but the current situation was that even the culture had already disappeared and there is no need for it, nor was there a market for it. Under such severe circumstances, I could not make a living only with my aspirations, so I developed tinware products with an “Okinawan touch” and created the foundation for our workshop operation today.

Suteacher,” a single-flower vase made of pure tin, takes advantage of the weight of tin.

Suteacher,” a single-flower vase made of pure tin, takes advantage of the weight of tin.

Its low center of gravity allows even tall plants to be arranged stably.

Not just a souvenir, but a way for people to“become familiar with tin crafts and learn more about Ryukyu tinware,” he says, “We have developed a ring stand made of a Chinanago,( garden eel) whose body can be bent into any shape, and a single-flower vase that takes advantage of tin’s weight and antibacterial properties. Now, the concept and high design quality are well supported, and orders are coming in from all over the country.

Engaged in the restoration of “Utamasuki,” a ritual utensil

The family crest of the Ryukyu royal family is “Utamasuki,” decorated with “Left Mithu-domoe (triple spiral).

The family crest of the Ryukyu royal family is “Utamasuki,” decorated with “Left Mithu-domoe (triple spiral).

Furthermore, the following year, he was able to engage in the restoration of a cultural asset, which had been a long-cherished dream of his. Without any hope that someone would take a look at it, the tin bottle that he had been researching and restoring on his own caught the eye of a researcher.

The tin bottle that he was commissioned to restore was an utamasuki, a drinking container used to fill awamori and offer it to the gods. The tin bottle is decorated with glass beads.

He restored it based on an existing cultural asset, but we could not disassemble such a valuable cultural asset. Therefore, he proceeded with work by calculating the weight and thickness of the tin inferred from the weight of a single piece of glass, and by observing the interior with an endoscope. He compared them with the existing Gotamonuki and made corrections, repeating the process to complete them. Moreover, because they were made in pairs, he had to make two identical pieces, just the same as the existing ones.

Thorough the restoration process., it was founded that Utamasuki was made from six partss.

Thorough the restoration process., it was founded that Utamasuki was made from six partss.

The restoration work made it clear that the metalworking technology of the time was extremely advanced, since it was possible to make such high-precision binshi(sake bottle) in the 1500s, when there were no electric potter’s wheels. I understand this because I am a craftsman myself”.

Reproduction of the Shudei, a Ryukyuan ritual utensil

A shudei actually arranged for drinking awamori.

A shudei actually arranged for drinking awamori.

Mr. Uehara also reproduced a Ryukyuan ritual tool called a shudei. It consists of a “jihai,” a cup with a handle decorated with a tree like pine and a container with a spout. It is the highest ranking drinking container for offering sacred sake (awamori).

A reproduction of an ear cup for ritual use, based on materials.

“The person who pours awamori into jihai(the ear cup), holds the ear part with both hands, prays, and pours it into the sake stand. The next person pours awamori into the ear cup and pours it into the sake stand, repeating the ritual. The awamori accumulated in this way is given to the people as usanday (hand-me-downs).

The ear part was held between the thumb and forefinger, and awamori was poured into the cup, and prayers were offered.

The ear part was held between the thumb and forefinger, and awamori was poured into the cup, and prayers were offered.

After it was no longer used in ceremonies, it was used as a dance prop by a few people, but this has almost disappeared.

Mr. Uehara not only uses the sake cups as cultural assets, but also creates sake stands that are arranged to be easy to use by using only one of the ear cups as a decoration, to convey the culture and charm of the sake cups.

Mr. Uehara’s recommended Sake snack is pickled wax gourd, a traditional Ryukyuan snack.

Mr. Uehara’s recommended Sake snack is pickled wax gourd, a traditional Ryukyuan snack.

Originally, awamori is an aged sake. When you actually drink old sake from this sake stand, you can understand why tin drinking containers were used for advanced ceremonial occasions. The silver-white color of the tin is beautiful and looks good in ceremonies, and while awamori is poured, it brings out the flavors even more clearly.

When you open the lid of the sake stand, the trapped aroma is softly released. When you bring the ear cup close to your mouth, you will feel the aroma again from the cup. This is because the surface of the sake cup has been finished with a brush mark that leaves an uneven surface to further deepen the depth of the aroma. The thinly cut rim of the mouthpiece is comfortable to the lips.

Ryukyuan “tee-gee” is an expression of reverence for nature.

A part which is corresponding to a ear of jihai.

A part which is corresponding to a ear of jihai.

There is a Ryukyuan word “tee-gee”, which means moderate.Rather than being precise and exacting in their craftsmanship, Ryukyuan crafts are characterized by retaining some of their natural forms.

I think that is why it is difficult to get a fair evaluation. This is not to say that they did not have the skills to create elaborate works of art. Through the restoration of cultural properties, I have learned that they had advanced technology. It is clear that they did not dare to do so, even though they should have been able to do. Mr. Uehara showed us a sake cup made of tin and coconut, which is said to be made by Mr. Oshiro Taru, the last tin craftsman “Shirkanizek” under the direct control of the Ryukyu Dynasty. Oshiro’s works were also exhibited at the National Industrial Exhibition promoted by Toshimichi Okubo in the early Meiji period (1868-1912), indicating that he had high skills and excellent sensibility.

Traditional Ryukyuan crafts.

Traditional Ryukyuan crafts.

The palm wine containers on the far left and middle right are palm wine containers presumably made by Mr. Oshiro.

I think this is the very work that embodies the Ryukyuan ideal. It is a combination of palm and tin, but it naturally retains its palm shape. The people of Ryukyu, who had long been threatened by typhoons, knew that nature was great and that no man could compete with it. Therefore, they probably had an underlying sense that the extent to which humans could create something was insignificant, and they probably made their products with a low level of craftsmanship.

It is a mistake to think of “tee-gee” as “not thinking things through. Today, the word “teige” is often used with the less favorable connotation of “laxity,” but I believe that “teige” was originally an expression of reverence for something beyond human knowledge.

Or, as in the case of Nikko Toshogu Shrine, there may be an idea that “when you are full, you will lack,” says Uehara.

Nikko Toshogu is said to be incomplete. For example, one of the pillars of the Yomeimon gate is upside down. It is said that this was done on purpose, because the decline of the shrine would begin as soon as it was completed.

Thoughts on what is being lost

Aluminum pot “Simmenabi.

Aluminum pot “Simmenabi.

It used to be sold at home centers in Okinawa Prefecture as a daily commodity.

When I first encountered Ryukyuan tin culture, tinware had almost been forgotten. I saw ritual tools, which were supposed to be valuable cultural assets, left in a damaged state. Unable to overlook such a situation, I moved to Okinawa with the determination to open a workshop and see if thorough until my dying day. My encounter with the last pot maker also encouraged my decision.

After the war, the “Simmenabi” aluminum pots supported Okinawa’s food culture and dye industry. After the war, when iron was not available, they were made from the wreckage of fighter planes. However, a few years ago, the last craftsman went out of business. Mr. Uehara had an exchange with him, and he shared the sand used for casting and was taught by him the process.

Casting sand for shared by an aluminum pot craftsman.

Casting sand for shared by an aluminum pot craftsman.

He also learned how to select sand, which he uses to restore cultural assets.

“I felt sad to see it disappear without being noticed,” he said. I wondered if that was the case with tin 100 years ago. I believe that manufacturing is closely related to “people, things, and places. I would like to continue my efforts in manufacturing and conveying the history of Ryukyu tinware to the present day, while valuing these connections.

Coverage cooperation : Toshinobu Uehara, Gold smith Mathu

Photograph and document: Gold smith Mathu

Write and shoot: Yuuko Setoguchi